Figure 1

Excerpt from Junji Ito’s Uzumaki.

I was at a dinner party recently with a few friends—ranging in age from 21 to 34—and we got on the topic of our latest reads. I offered up my current re-read of Murakami’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, while my journalist and longtime writer friend gave a more surprising answer, Junji Ito’s Uzumaki. Jimmy is the type of writer who can rattle off any author and their Wikipedia page at the drop of the hat. If he hasn’t read it, it’s on his list. But we’ve never discussed comics. In fact, no one at the table and I had discussed comics with one another. But when Jimmy said Uzumaki, we all knew to what he was referring.

In case you’re unfamiliar, Uzumaki is the title of manga author Junji Ito’s acclaimed horror series. It’s likely if you haven’t read the series, you’ve at least seen someone with a tattoo of Azami Kurotani, the faceless gal pictured above. Uzumaki, published in 1998, has earned numerous accolades and a solid place in pop culture history. However, had it have been written in 1955, it’s unlikely it would have been published at all.

The CCA and Fear Mongering

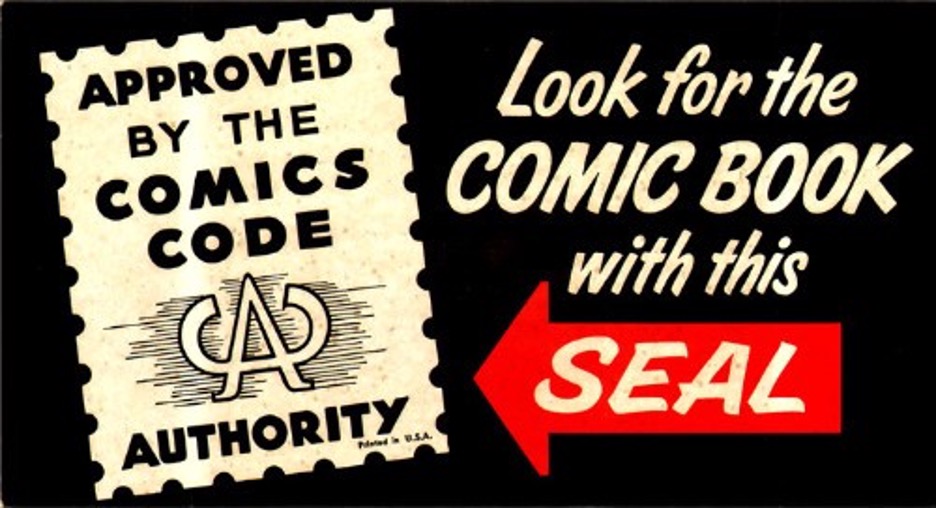

Figure 2

50s marketing image for the CCA

The 50s in America, what a time. Marked by the dawn of The Cold War, a booming economy, and white picket fences, the 50s were white America’s glory days. However, rising tensions with the Soviet Union led to a heightened sense of fear—also known as The Red Scare. A major aspect (motivator) of The Red Scare was Joseph McCarthy and, subsequently, McCarthyism. Joseph McCarthy was a Wisconsin senator who rose to political prominence in the early 1950s. He’s best known for his severe tactics when searching for and punishing those believed to be communists, and his name has since been associated with fearmongering.

The period known for McCarthyism is 1950 through 1954 and at the same time another kind of hysteria was percolating as well. Scott McCloud brings this period up in his text Reinventing Comics, saying “In the mid-50s the book Seduction of the Innocent by psychiatrist Fredric Wertham helped trigger a firestorm of anti-comics hysteria” (McCloud, 86). In the 40s and 50s, there was a purported notable uptick “juvenile delinquency” (Carrion, 2016). Much like the current argument for violent video games being linked to school shootings, people began to theorize it was because of violence in comic books. In 1954, hot on the heals of McCarthyism, the Comic Code Authority (CCA) was created in an effort to dull down violence in comics. The CCA took an axe to the metaphorical tree that is horror comics. But moreover, they effectively, for lack of a better term, nerfed comics across the board. A few of the rules outlined in the CCA include:

- Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal, to promote distrust of the forces of law and justice, or to inspire others with a desire to imitate criminals.

- No comics shall explicitly present the unique details and methods of a crime.

- Policemen, judges, Government officials and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.

- If crime is depicted, it shall be as a sordid and unpleasant activity.

- Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates a desire for emulation.

- In every instance, good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

- Scenes of excessive violence shall be prohibited. Scenes of brutal torture, excessive and unnecessary knife and gunplay, physical agony, gory and gruesome crime shall be eliminated. (SCG, 1955)

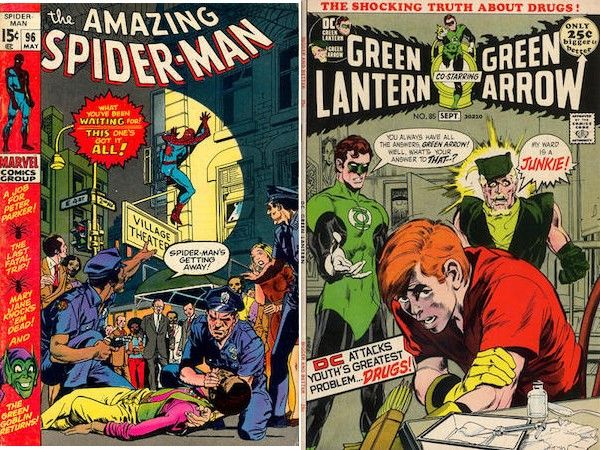

These rules didn’t just take on violence or gore, they took on the context that would justify that content. Comics following the CCA were devoid of controversy and typically pro-cop. Consider the image below of two CCA approved Marvel Comics,

Figure 3

CCA approved comic book titles

Needless, the relevancy of the CCA was not well maintained. The code was revised in the 1970s to allow more shows of violence and sensuality, and by the 1980s it was completely defunct. It’s impact, however, was long-lasting and deeply stigmatizing.

Post CCA Comics

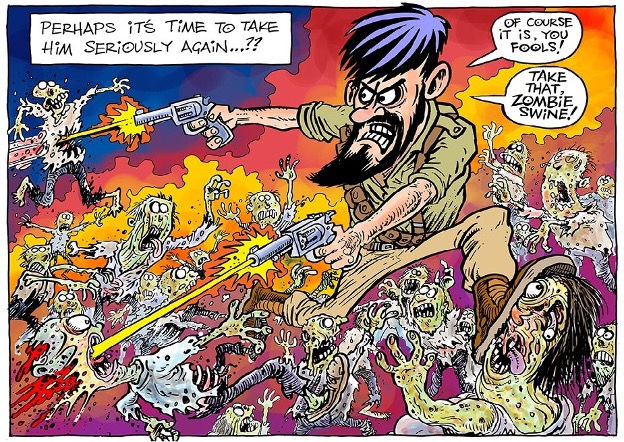

Figure 4

Underground Comic by an Anonymous author

In his text The Horror Comics: Fiends, Freaks, and Fantastic Creatures 1940s-1980s, William Schoell (2014) states “horror comics were all but obliterated by the comics code” (Schoell, 1). This is demonstrated by the notable lack of anything resembling horror in the mainstream post-CCA landscape. However, prior to this, horror was a popular genre in the world of comics. Authors Peyton Brunet and Blair Davis (2022) touch on horror comics specifically in chapter four of Comic Book Women, saying, “weird tales of horror and suspense were formative to the development of comics’ Golden Age. From the late 1940s through the mid-1950s, dozens of horror comics with titles promising strange, forbidden, terrifying, startling, weird, mysterious, and unusual stories flooded onto the market from nearly every major comic book publisher.” (Brunet/Davis, p. 111) In the wake of the CCA, an entirely new underground comic scene emerged depicting lewd content. Yes, the weird artists couldn’t stay muzzled for long, and in the 60s and 70s they published comics independently and told their stories uncensored. Many of these comics were satirical in nature and commented on society, the very society that was trying to silence them. You may be wondering, though, when did horror come back into the mainstream?

Horror comics appeared in the mainstream as early as 1972 with titles like The Drifting Classroom by Kazuo Umezu. Essentially, after the 1960s the CCA had little effect on publishable content and authors could create what they wanted.

A Bloody Good Return

Figure 5

Excerpt from Kazuo Umezu’s The Drifting Classroom

Now, this may be more opinion than fact, but horror comics are some of the best on the market. You’ve got Junji Ito creating surreal scares and new authors like Haruto Ryo playing on classic horror tropes but creating something entirely new. Perhaps their livelihood being threatened by the CCA or the taboo motivators coming from the underground scene caused them to come back with fervor, but horror comics have become some of the most innovative and artistic on the market. Now, if you need something to boast about at your next dinner party, regale your friends with the long, twisted history of horror comics and regulation.

References

McCloud, Scott. Reinventing Comics: How Imagination and Technology Are Revolutionizing an Art Form. HarperCollins Publishers, 2002.

Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Comic Books and Juvenile Delinquency, Interim Report, 1955 (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1955).

Brunet, Peyton, et al. Comic Book Women: Characters, Creators, and Culture in the Golden Age. University of Texas Press, 2022.

Schoel, William. The Horror Comics. McFarland & Company, Inc., 2014.

Carrion, Tho. “What Was the Comic Code?” Medium, Medium, 23 Sept. 2016, https://medium.com/@supertho/what-was-the-comic-code-6d6c4d08644

“McCarthyism.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2022, https://www.britannica.com/topic/McCarthyism.

History.com Editors. “Cold War History.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 27 Oct. 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/cold-war/cold-war-history

Provide Feedback

You must be logged in to post a comment.